Whenever I’m leading tours around Germany or just exploring Europe with friends, I always make an effort to point out the Stolpersteine we pass. At which point they always ask: “What are Stolpersteine?”

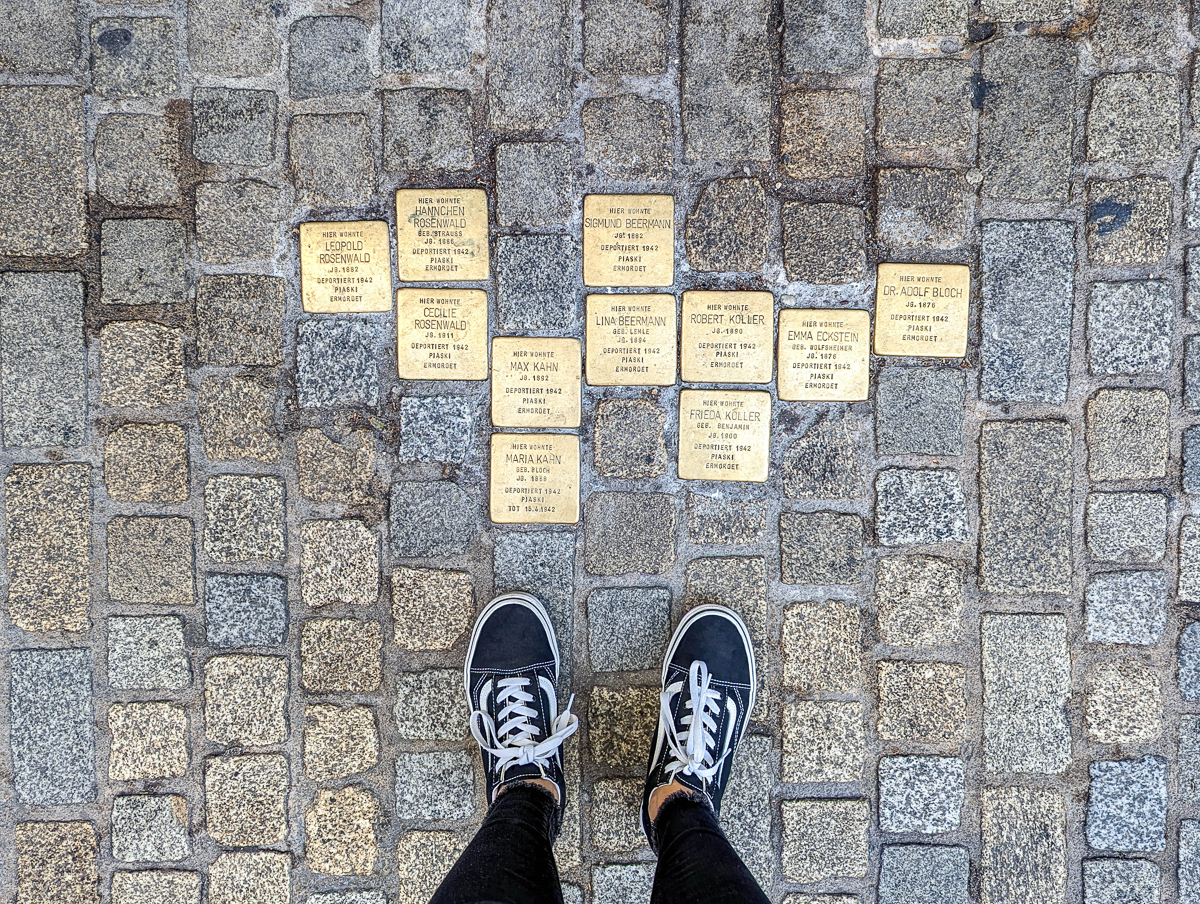

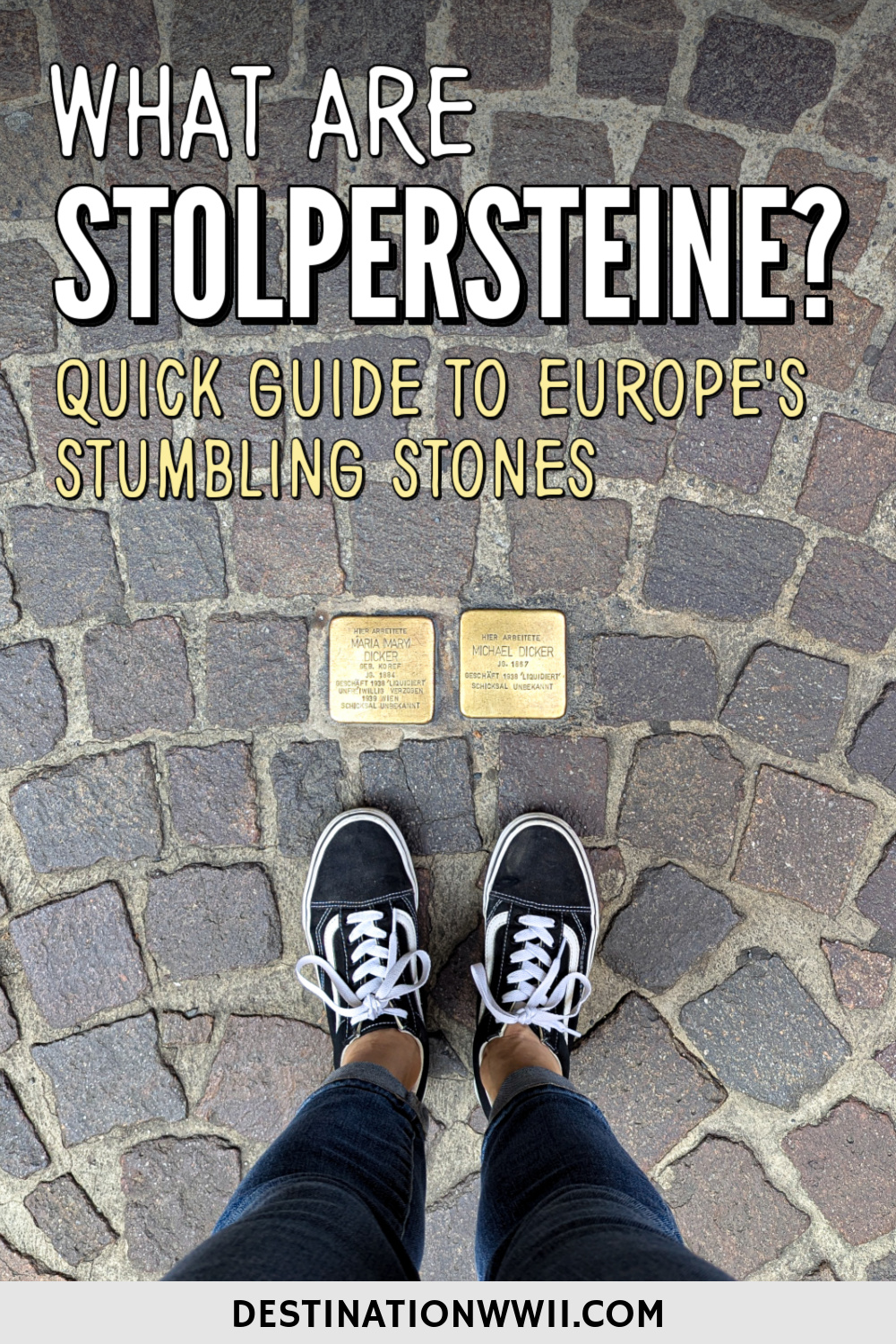

I mention Stolpersteine (“stumbling stones” in English) in just about every post on this blog when discussing World War II sites in particular cities. I give a very brief explanation each time, but I want to talk about them a little more so you have the whole story ready to go when you see one. (And you will see one!) Prepare to see a lot of photos of my feet…

What are Stolpersteine?

Simply put, Stolpersteine, or Stumbling Stones, are small Holocaust memorials. Each one commemorates a particular individual killed in the Holocaust and contains a small bit of information about them. These 4×4” brass cobblestones are usually inlaid in the ground outside that person’s last known residence. (Though they can be placed in other places as well.)

The information each one contains can vary, but typically Stolpersteine include:

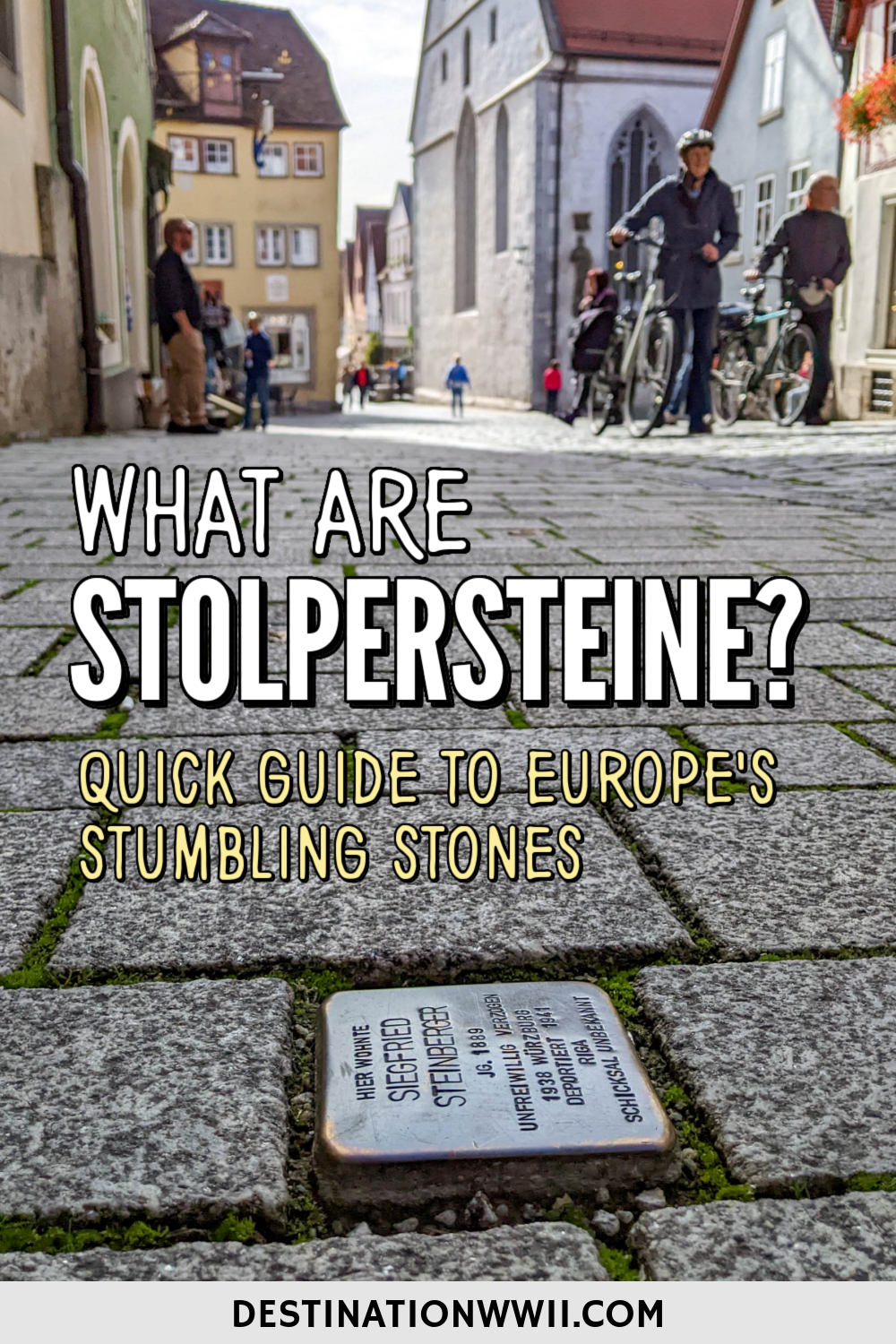

The information on the stones is minimal, but that’s part of the artist’s intention. In many cases, you can find further biographical information about that person online or on the city’s Stolpersteine website (if available). The stone on the left in the photo below says:

Here lived

Siegfried Süss-Schülein

Born 1903

Deported 1941

[to] Riga-Jungfernhof

Kowno / Kaunas

1944 [to] Dachau / Kaufering II

Murdered Dec 11, 1944

The Talmud (the primary source of Jewish religious law and theology) says: “A person is only forgotten when their name is forgotten.”

About the Stolpersteine project

Stolpersteine are the work of Gunter Demnig, a prominent German artist whose work centers around politics and protest. Looking for a way to commemorate the lives of millions of Holocaust victims, he devised the Stolpersteine concept in 1992/1993.

The city of Cologne (Köln), Germany laid the first Stolperstein on December 16, 1992 in front of its City Hall. Rather than highlighting a particular victim, this one includes the text of the “Auschwitz Decree”–Heinrich Himmler’s order to begin deportations of Jews to the death camps.

Since then, Demnig and his team have installed over 116,000 Stolpersteine in 31 countries and nearly 1900 cities (as of 2024). That number continues to grow each year. And even though that’s a huge number, never forget that the Nazis killed an estimated 11 million people (6 million of which were Jews).

Who are Stolpersteine for?

“All victims persecuted or murdered by the National Socialists” are eligible to receive a Stolpersteine. This includes not only Jewish victims, but also Roma, Sinti, and those persecuted because of their religion, political affiliation, sexual orientation, skin color, physical or mental disability, and more.

How does someone get chosen for a Stolpersteine?

So how do they decide who gets a Stolperstein? Anyone can fill out a request to have someone commemorated with a Stolperstein. Typically, that person will be a surviving member of the victim’s family, though it can be anyone from the general public. Even you can sponsor one!

The person requesting the stone does their own research on the individual being commemorated and gets to choose what the inscription will say (based on a general template). Producing and installing a Stolperstein costs between €120 and €180 (depending on location) which is generally paid through donations, sponsorships, or the families themselves.

Where to find Stolpersteine

Demnig and his team have installed over 116,000 Stolpersteine (and counting) in 31 countries, all in Europe. As of 2025, you can find Stolpersteine in:

Some countries have a ton of them; some have very few. The country with the most is Germany, by a mile (more than 80,000). Berlin alone has 10,000. The entire United Kingdom has just one.

Where you won’t find Stolpersteine

There are a few places in Europe where you won’t find any Stolpersteine, and that can be for a variety of reasons. In order to get a Stolperstein installed, you must have approval from the city since they are, most of the time, installed on public land. And though Stolpersteine are widely and enthusiastically accepted, some cities have prohibited them. Paris is one such city; Munich is another.

Stolpersteine in Paris

In Paris, the City Hall’s Memory Officer believes the stones “reflect an image that is not appropriate for France” and attributes this to the fact that “The Jews have not disappeared from France; they are still present.” In other words, because, as he states, 75% of the city’s Jews survived, commemorating the 25% who didn’t is neither worthwhile nor a good look for Paris. Yikes.

Paris, a city that capitulated to the Nazis after just 39 days of resistance, that agreed to a collaborative partnership with Nazi Germany, and that finished out the war as the capital of Vichy France (the Nazis’ puppet regime) would prefer to sweep their unsavory past under the proverbial rug. Go figure. (I will also take this moment to remind you that Stolpersteine are not merely a “Jewish thing”; they are used to commemorate all victims of the Nazi regime, even some who were persecuted but not killed, as shown above.)

Check out the Facebook page Stolpersteine in Paris for more on the civilian efforts to bring these memorials to Paris and much more.

The compromise

In lieu of Stolpersteine in Paris however, you can still find a version of memorial plaques around the city. These are typically subtle white marble plaques on the sides of buildings. Unlike the Stolpersteine which include the harsh details of the person’s fate or execution, Paris’s memorials display only vague information with a person’s name and the fact that they “died.”

See more Paris World War II sites here.

Stolpersteine in Munich

The other major city to disavow Stolpersteine is Munich, Germany. Munich, the city that raised Hitler and birthed the Nazi Party, that incited Kristallnacht and executed its student resisters, continues to uphold its ban on Stolpersteine. Go figure.

But the situation in Munich is a little different. Unlike with Paris, Munich’s main voice of contention comes from Charlotte Knobloch, leader of the city’s Jewish community, former president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, and herself a Holocaust survivor.

Knobloch argued (in 2004) that walking over the names of Holocaust victims, on stones that would get dirty, would be disrespectful. Fair point, I guess? But by her logic, how is the absence of a memorial any better? It’s also worth noting three things about Gunter Demnig’s initial purpose for this project:

- Being brass, the stones are able to be polished by friction, meaning the more people walk over them, the shinier they’ll be.

- While visiting the Museum for Sepulchral Culture in Kassel, Germany, Demnig asked their thoughts on walking over grave slabs (like the ones inside St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome). They explained that this is actually a special kind of honor. “The more people walk over the grave slabs, the higher the recognition of the person buried there,” they said.

- One must bend down in order to read the stones which represents a symbolic bow to the victims.

An unfair ban

Something else I’d like to add is that, yes, there are Holocaust memorials all over the world already, including Germany. But Stolpersteine are something truly special in that they are an exclusive monument dedicated to one singular individual. That person gets their own memorial, installed at the last place he or she lived a free life.

Family members who have laid stones liken it to a belated funeral and are eternally grateful for the opportunity. Banning Stolpersteine means depriving that person and that person’s family of that honor while the rest of the continent gets to cherish theirs.

The compromise

It’s also worth noting that the current President of the Central Council of Jews in Germany (Josef Schuster) strongly supports the Stolpersteine project, as do the 102,000 people who signed a petition to lift Munich’s ban. Neither of those were enough to change the city’s mind when the ban came up for another vote in 2015.

Instead, they compromised with a different kind of Holocaust memorial around town which began being installed in 2018. You can now find shiny gold-plated stainless steel memorial plaques in certain places around Munich. Similar to Stolpersteine, they typically include the person’s name and some brief information, and even an artistic rendition of a photo. These are placed either on or near the person’s last known residence. Charlotte Knobloch is satisfied.

See more Munich World War II sites here.

The arguments

After the city of Munich upheld its Stolpersteine ban in 2015, Munich attorney Hannes Hartung filed a lawsuit on behalf of a group of notable supporters. Apparently, the “right to individual remembrance” is enshrined in Germany’s constitution and the Stolpersteine ban violates that. Regardless, the courts dismissed the lawsuit. Shocker.

Supporters of the Stolpersteine project also defend their positions by reminding the city that ground-based monuments have long been a part of Munich’s remembrance culture. The most famous of these is the White Rose memorial outside the entrance to Ludwig Maximilians University which includes copies of the group’s pamphlets on the sidewalk.

There’s also the Monument to the Gays and Lesbians Persecuted Under the Nazi Regime which consists of different colored painted shapes on the sidewalk, the sidewalk memorial to Georg Elser (executed for trying to assassinate Hitler) at the location of the former Bürgerbräukeller, and the Visgardigasse memorial behind the Feldherrnhalle which is literally formed by bronze cobblestones on the street. Seeing as how none of those are dedicated to Jews specifically, I guess Charlotte Knobloch doesn’t have a problem with them.

The defiance

Regardless of the ban on Stolpersteine, supporters of the movement continued to sponsor the stones. They would pay for them, create them, and then store them in a city cellar until they could do something with them (245 in all).

Jewish resident Terry Schwartzberg, who has been the chairman of Munich’s Stolpersteine committee since 2011, then formed the Stolpersteine for Munich Initiative to give these stones their proper homes. The loophole? Munich’s Stumbling Stone ban only covers public ground, not private.

Now, with permission from Munich’s residents and land owners, the Initiative has installed over 420 Stolpersteine around Munich (as of July 31, 2025). This “private ground” includes areas like driveways, thresholds, church grounds, and any other area not owned by the city. This is why you can still find Stolpersteine all over Munich, despite the ban.

Paris has also bypassed the municipal ban and installed Stolpersteine on private ground, though their numbers are far fewer than in Munich.

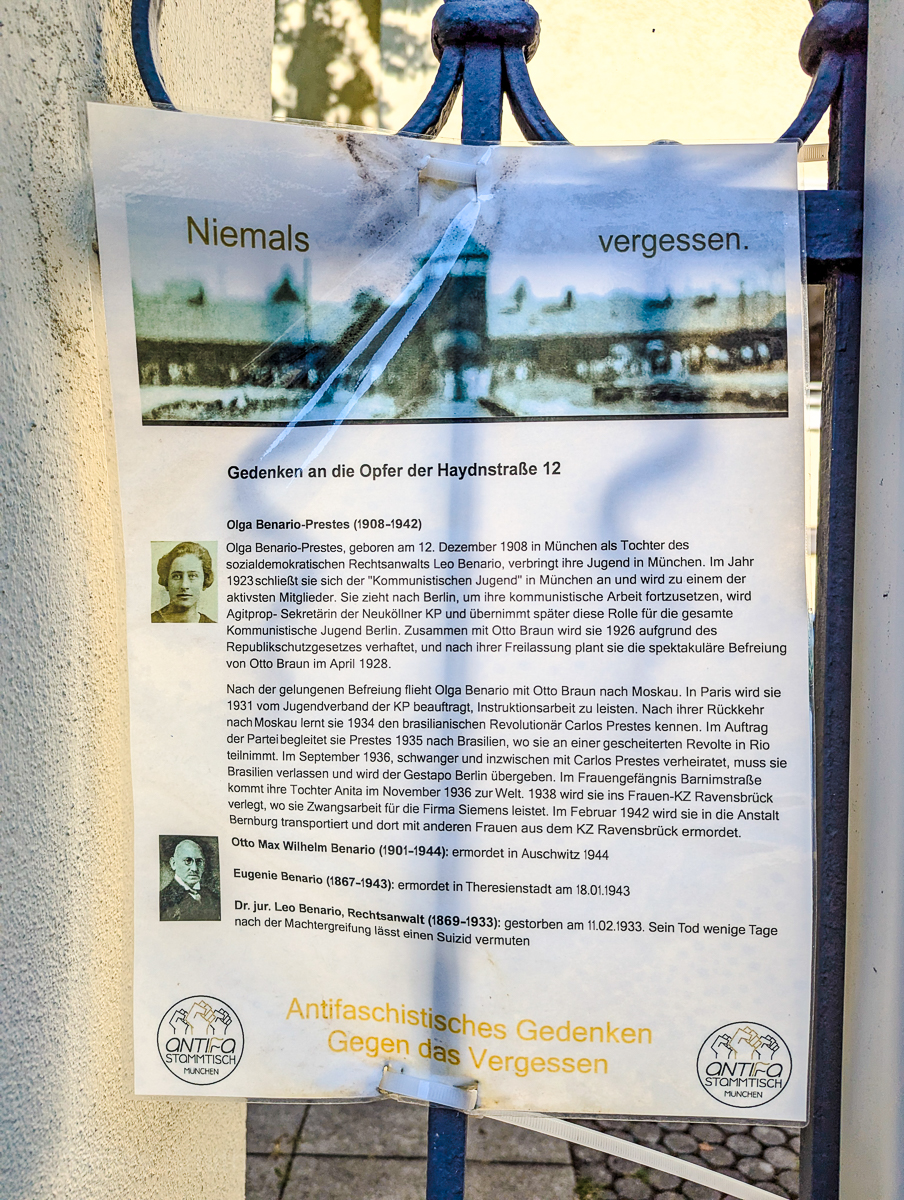

As seen below, some of the stumbling stones that have been placed in Munich also come with biographical information on the people being commemorated hung up near the stones’ locations. This is at Haydnstraße 12 and, in my opinion, proves how much the citizens of Munich actually appreciate this project.

How to find Stolpersteine

Now that you know all about Europe’s Stumbling Stones, you’re probably wondering where you can find some yourself. Since no official complete database yet exists with all their locations (though they’re working on that!), you have a few different options…

First, some cities do have dedicated Stolpersteine websites with such information and even interactive maps. When I find these, I consider it a treasure trove. Not all cities with Stolpersteine have these, but some of the cities that have lots of them do. Some examples are:

Other ways to find them

When a certain city doesn’t have its own dedicated page, I have to turn to other sources. The key is knowing what Stolpersteine is in other languages. You may know them best as Stumbling Stones. Throughout the German-speaking world they are Stolpersteine. In Italy, they’re called Pietre d’inciampo. In France and Belgium, Pavés de Mémoire. So, if your search for “Stolpersteine in Rome” doesn’t deliver, now you know why. (Be sure to use the local spelling of the cities too.)

Wikipedia

Wikipedia has some Stolpersteine articles for certain cities, though some are often outdated and the accuracy is hit or miss. Some examples are:

News articles, Facebook, & Google Maps

I’ll also do searches for news articles that mention the installation of a stone somewhere to see what information I can find. Some local Stolpersteine groups have their own Facebook pages or groups you can join where they share information. For example:

If I find a photo of one without any other information, I’ll research that person’s name to see if I can find an address associated with them. After finding an address, I plug it into Google Maps and see if I can see any stones using Street View. If I can, I mark that address on my own map for when I get there. (I spend an unholy amount of time on Google Maps.)

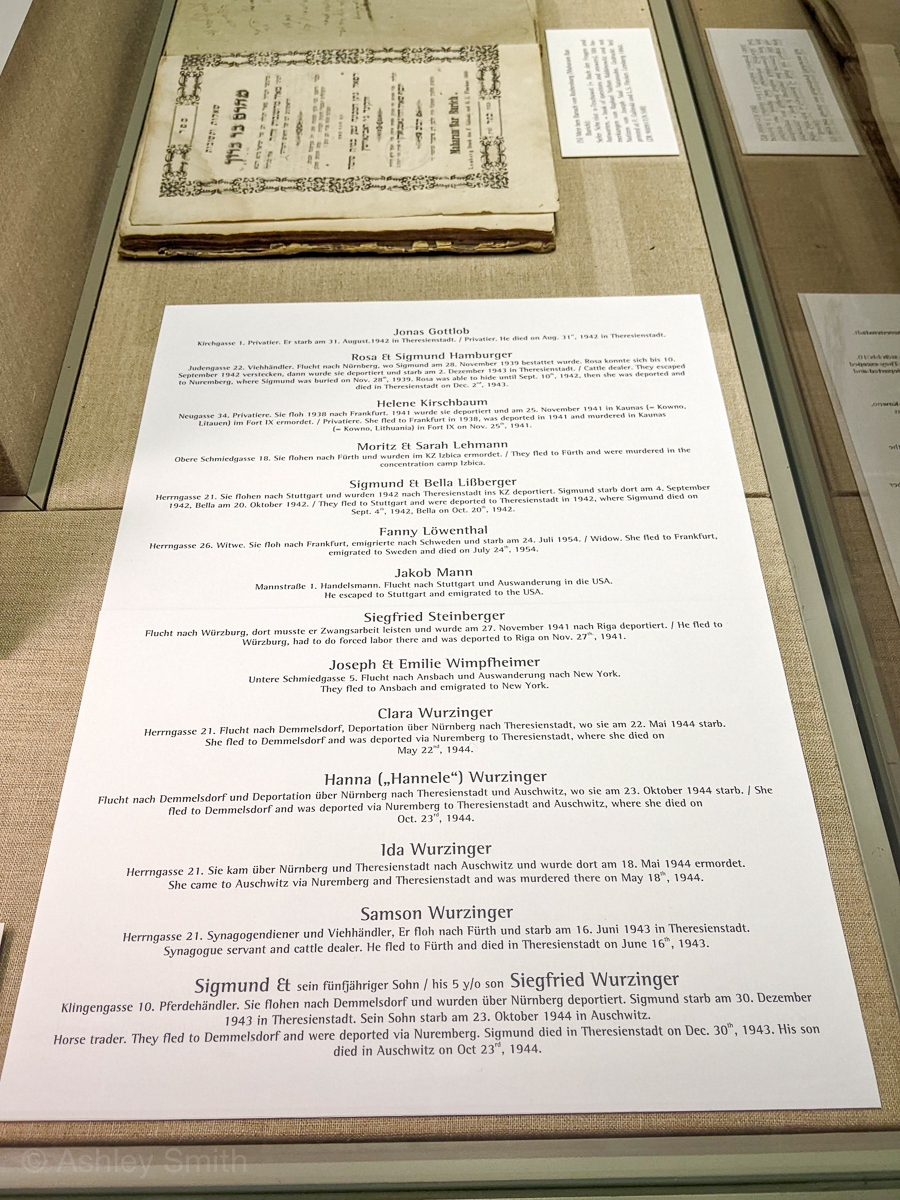

you might have to Get creative

In Rothenburg ob der Tauber (Germany), in the basement of the Rothenburg Museum is the Judaica exhibition. And in that space is an exhibit on the persecution of the town’s Jews during the Holocaust. One of the artifact cases includes a list of said Jews along with some brief biographical information and their former addresses. I saved the addresses of these 19 people and walked around town to each of them to see if I could find a Stolperstein. And at most of them, I did.

In some cities, there are so many Stolpersteine all you have to do is keep your eyes towards the ground, know what to look for, and walk through the right areas. Stick to historic town centers and Jewish quarters for your best chance at spotting one in the wild. This happened on my most recent trips to Prague and Bamberg. Without even trying I came across stone after stone after stone.

Some helpful travel info

- Hotels: Find great places to stay on Booking.com (my go-to). Expedia and Hotels.com are worth checking too. VRBO is best for apartment rentals.

- Rental cars: Check out the best rental car deals here.

- Local tours & activities: Check out all the great local options from Viator and Get Your Guide here.

- Don’t forget a helpful guidebook and one of these must-have customs and culture guides!

Like this post? Have questions about Europe’s Stolpersteine memorials? Let me know in the comments below. Thanks for reading.

Save this info, pin this image:

Thank you for the very informative post, we will be on the lookout for them when we visit the Netherlands and Belgium next week!

Awesome, have a great trip Jason!